RxOH 2022 Alum: Huan Dong

Huan Dong

“The forest and the land will reveal the stories of the weather and animals that have interacted with it...”

As Terri oriented us to the various plant species on our hike, she reminded us that we can often find clues of natural processes and human or animal activity by observing the details of the surrounding land. Some clues are physical objects that have remained for decades, like rusty metal gears left from old natural resource production machinery or animal bones; while other clues reflect academic and technical ideas from scientists – not unlike those among the group – as she pointed out the visual difference in tree density between the natural groves and the xxx groves? All this was set to the gorgeous background of the Red Clover Valley, as part of the first leg of the “Sierra to the Sea” theme of our Rx One Health 2022 Field Course. This was historically a logging valley, then a ranching valley, and once almost a fancy golf resort, though now an ecological land trust that was nearly decimated by the forest fires which raged across northern California just last year.

Many of us, especially those who have lived or received education in California, were recently well aware of how the forest fires impacted our daily lives, from the poor air quality to changing weather patterns, and evacuation of neighborhoods. Yet fires are not universally “bad” for the environment as many may think. In fact, some plant species have evolved to utilize fires as environmental cues for survival, such as the Aspen, whose seeds need the heat from the fire to help initiate the germination of their seeds. As a group discussion, we were also able to dive deeper into the various scales of forest fires, from slow-burning brush fires to rapidly spreading high-heat fires which have different impacts on the nearby land and animals. I found these science-based discussions incredibly engaging and much more conducive to collaboration and potential policy planning than the rhetoric put forth by politicization efforts that are so prominent in today's new cycles. Even as my memory retains small tidbits of our discussion that day, I came to better appreciate the land and environment that I previously thought I was familiar with. I grew up in Northern California and have visited Tahoe or the surrounding Sierras multiple times before, but never was I able to appreciate the land as much as I came to on this trip. Everything felt a little more meaningful; from the sky, the grass, the flora, and even the fauna, as we saw coyotes, cattle, and even bears crossing the valley in the distance

Taking a peek at a distance and keeping a close eye on interspecies interactions was also a large part of our activities in the valley. As we have all recently experienced and continue to experience the enormous public health and economic impact of a respiratory virus spillover event between two species, it is probably a smart idea to keep an eye on some of the animals that live among us. As I was just weeks shy of starting my first year of a Pediatric Infectious Disease fellowship, I knew I would be exquisitely excited as we discussed infectious diseases surveillance and epidemiology. Though the perspective of the discussion was the opposite of my usual approach as a medical doctor diagnosing and treating infectious diseases, the perspective we took was from the viewpoint of the population dynamics and health of field rodents.

Led by Dr. Brian Bird, who had previously conducted veterinary surveillance fieldwork during the Ebola outbreak in Western Africa, we learned some technical aspects of how to monitor, live-capture, collective specimens, and release field rodents for active surveillance. Knowing that there are incredibly smart people out in the field monitoring these rodents for viruses or other potential pathogens, I feel a little more reassured about the next potential pandemic (though it’s still scary!). We learned how there are numerous challenges in doing this work, including wearing personal protective equipment in over 90’ degree weather while handling very tiny rodents. We also heard from Dr. Robyn Stoddard, a research microbiologist currently at the CDC, who coordinates sample processing from projects and responses from all over the world in various conditions.

Along this vein, we also discussed the important differences between urban and rural communities that impact the spacing and distribution of humans with other mammals including rats, rodents, chipmunks, and even bats. Bats, though not always readily recognized in human settings because of their stealthy nature, are incredibly important species to monitor due to their unique immunologic physiology with relatively high potential for transmission of pathogens to humans. The more we are able to learn about them and their natural behaviors, the more we can share and disseminate educational materials to help mitigate the human behaviors which could help reduce contact, thus helping entire rural communities avoid repeated transmission events that could lead to an outbreak, which had previously been done as part of the work of Dr. Bird and team.

In addition to all the exposure to aspects of veterinary medicine on the course, we also had the opportunity to exchange ideas and stories to foster human connections with each other. Many of us are science and health-based trainees who were all very used to working in our segregated fields without much inter-sector discussion. Thus there was ample room for exchange of ideas when we had 25 young minds representing 11 different nations with backgrounds in public health, medicine, veterinary medicine, ecology, virology, social and laboratory sciences; a spectacular selection of individuals by the course directors, Dr. Jennie Lane and Dr. Woutrina Smith.

On the first day of the course, before we even left to set up our tents in the Sierras, I met a young curious medical student from the SF Bay Area, named Julio, who was now attending UC Davis School of Medicine. We quickly sparked conversations about the intensity of medical training and the importance of holding onto our roots and motivations for joining the field of medicine, as we have seen the impact of the arduous training on friends and colleagues who have burnt out to become another jaded cogwheel in the industry of healthcare delivery in this nation. We both had previously traveled to the United States with our families many years ago and feel incredibly fortunate to have been able to overcome barriers to becoming medical providers. With our varied experiences, we both sought ideas to improve the health of communities from which we came by reducing the social and systemic prejudices that remain among Latinx and Asian-American communities, even in a place like California.

To our amusement, we ended up both sneaking some pictures of each other as we sat and reflected on our individual journeys. At that moment, when we came across a large open grass and flower field which was a break between patches of conifers, I was overwhelmed by emotion. I was so saddened to hear that this grove almost did not survive the forest fire from last year, emphasized by the fact that I could still see the soot on the ground, the blackened desiccated bark of large swaths of trees, and even large holes in the ground resultant of fires burning so hot as to completely burn through root systems of large coniferous trees. That moment and that experience almost never existed if one of the large fires from last year had just burned another 20 or 30 feet. As I slyly cried in wonderment from underneath my sunglasses, I thought about how peaceful I felt in that field. I felt that I could breathe, I felt that I could be at ease, and I felt a sensation of rejuvenation and of healing. Maybe it was from the culmination of the science and social experiences I had recently, however it wasn’t just me. Julio felt it too, the healing energy from the field. We spoke to each other about the urban and sub-urban environments in which our families and patients reside, some of whom will never have the opportunity to experience the natural splendor of what we were witnessing in that moment. We wondered how much of this healing energy we felt could benefit our patients, or our families and communities. Studies have demonstrated the healing impact of plants and green spaces on hospitalized patients recovering from illness or surgery. There are also new approaches to helping patients understand environmental impact and interconnectedness, especially in our younger population in which obesity and chronic overnutrition have severe impacts to our nation’s health and future productivity. We wondered if we would one day prescribe tickets to national parks and guidance on hiking instead of multitudes of pills and tablets that patients take as they continue on their sedentary lifestyles, as some providers have already started to explore.

Beyond our exchanges and our academic discussions, the course was full of physical based activities such as waking up early in the mornings to check rodent traps, trekking through different terrains, and shielding ourselves from the “excessive sun” as one of our colleagues put it. One of my favorite activities was measuring water flow through a stream using various methodologies and instruments. In our sessions with Dr. Miles Daniels from UC Santa Cruz, we learned some of the factors that impact the dynamics of the watershed in the Red Clover Valley. Hydrology and water sciences were more relatable than I previously imagined, as I used terms such as “laminar flow” to describe what we were observing, as opposed to when I usually use those terms to describe air entering a person’s respiratory tree or blood flowing through a human artery. We were able to understand each other as that foundational basic science concept of fluid dynamics remains the same. It also was interesting to discuss in depth the implications of such a valuable and finite natural resource that needs to be shared among so many spaces, plants or crops, animals, and humans all throughout California. Some of the water I was measuring, would eventually flow all the way to places like Los Angeles, where I live, thus it is ever so important to understand that journey from the water sources to its destination. Water that carries poisons, toxins, or pathogens could harm so many along its path, thus it was incredible to hear about some of the projects that doctoral students or post-doctoral fellows are conducting to look at how artificial or natural dams (from beavers) could impact the distribution of pathogens that can cause acute and severe diarrhea. At times, I wondered if physicians who interface with sick patients ever think about the sources of the pathogens. Of course, as a budding infectious diseases fellow, my interest peaked. Could we use the study of physical water flow dynamics to potentially design and mitigate the transmission of water-borne pathogens? Perhaps this was inspired by the learning that the Western Fence Lizard is able to sterilize ticks of the Borrelia bacteria, thus mitigating the potential for Lyme disease transmission in humans in California and the west coast. Should we be monitoring these lizards also, because if their numbers dwindle or change, would we see an associated change in the incidence of Lyme disease in our clinics and hospitals?

Some of the water that we measured will eventually flow to the San Francisco Bay and out to the Pacific Ocean, which was the setting of the next leg of our journey. We had the opportunity to stay in the Monterey Valley and experience both the surrounding farmland as well as the boundaries of the land, seawater, and freshwater.

Part of that freshwater is also needed to maintain California's robust agricultural industry, which is termed “the Salad Bowl” of the world because of its prolific production of leafy greens and lettuce among other crops. As many Californians know, this distribution of water flow and water rights is also an important discussion in the current political landscape. Understanding the science of water allocation as well as improving on agricultural techniques for less water waste is important as we continue to need nutritive food sources and freshwater supply for an expanding human population. We had the unique opportunity to visit Alba Farms, which hosts an education curriculum to support independence in agricultural production and vending, though, through this experience, we also heard first-hand about the health disparities and social anxieties that the mostly immigrant population endures. I found it quite unjust that some of the nation's poorest individuals work extremely hard in sometimes harsh conditions and lack of access to health care, all the while contributing to one of the largest economies in the world (California alone is the world’s 6th largest economy), and feeding organic, healthy foods to some of the nation’s most wealthy individuals. This is not an uncommon situation across the world, and our one health discussion focused on linkage to care and support for this population.

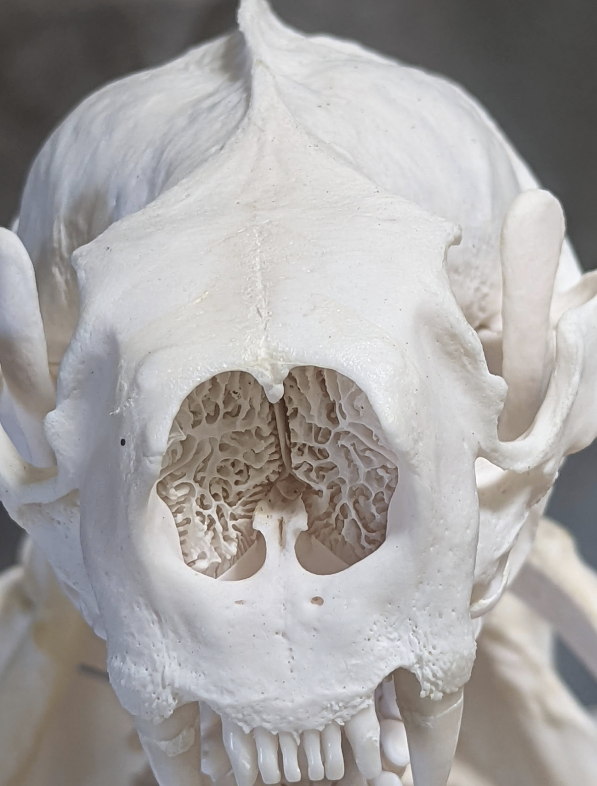

As the water continues towards the sea, there are birds, otters, and other species that live close to the shore, they’ve experienced drastic changes to their environment and – unfortunately – act as “sentinel species”, or species that potentially manifest the clinical consequences of illness before humans. In this case, sea otters live in a very sensitive and dynamic food chain cycle, which can be impacted by human pollution or human inconsideration. As we toured and discussed clinical cases at the Marine Wildlife Veterinary Care and Research Center in Santa Cruz, our One Health brains raced because it was a unique culmination of many concepts of animal and ecological health that we learned along our course. We discussed one case where human inaction to maintain adequate water and nutrient flow could lead to the proliferation of microorganisms in a small inland lake, which can produce toxins that then eventually make their way down to the sea, where the otter is constantly exposed. This process also piqued my interest, because hearing the cases, the workup, the laboratory details, and the images of pathology reminded me of my clinical practice of human medicine. My ability to understand veterinary medicine and ecological concepts stems back to the foundational basic sciences that all these fields are built upon.

Ultimately, this experience not only re-invigorated my potential to join multidisciplinary teams to work on large expansive environmental and health issues, but also re-invigorated the emphasis on solid scientific foundations of methodologies and discovery. In our current world of misinformation and disinformation, we must be vigilant to share and expand the importance of critical data interpretation, instead of distorting the data to benefit from capital gains. This points to the importance of how policymakers and political leaders need to have a better understanding of these issues, even from a fundamental elementary education level. This points to how we should be investing and improving our science education and knowledge, instead of shying away from it because it is variably complex and intricate to interpret.

So as we look towards the future, may Terri was onto something – we will leave our mark on this world. Will it be revealed to our future generations that we were able to work together to try to find solutions to our environmental and health issues, or will the future show that we missed our opportunities to collaborate and thus they are seeing the consequences of our inaction? How will Red Clover Valley look 100 years from now? Will the beavers return to build their dams? What about the health of the agricultural workers in our California coastal farms, how are their children? Will the coastal birds and mammals find happy niches to live or will our pollution and development destroy their natural habitats?

These issues often seem insurmountable, and they continue to be great challenges for our scientific communities… but after my experiences meeting bright and motivated individuals through the Rx One Health Field Course, I am inspired to move beyond the silos of our specialized fields to tell future generations the story that we were able to reach back to our scientific foundations and join forces to build a brighter future.